BY HOWARD YAHM

The most difficult impasses in mediation are generally based upon unresolved emotional issues within or between the parties. At these times, a mediator simply focusing on the facts or the content of the case cannot enable the couple to move beyond this stalemate; rather, the mediator must often understand their emotions in order to break the impasse.

We have come to recognize that divorce is a regression inducing experience resulting in heightened emotions that would not normally be typical for the person. We need to learn how to approach these emotional reactions without performing psychotherapy.

The term regressed in this context means that people are re-experiencing aspects of earlier events and reacting to them and functioning on a younger or earlier developmental level than they might otherwise were they not experiencing the multiple stressors of the divorce process. Separating or divorcing adults encounter a number of predictable emotional experiences which can be placed on an emotional range or continuum. At one end of the continuum is a mild and predictable experience that any individual undergoing a separation or divorce might have while at the other end of the continuum is an extreme or even pathological reaction due to the regression involved.

Five of these emotional ranges will be discussed and analyzed in the framework of how they would manifest in someone undergoing a mediated divorce as compared to an adversarial divorce, and different models of mediation will be utilized to examine how mediators can approach these emotions in powerful ways without doing psychotherapy.

EMOTIONS RELATED TO DIVORCE-INDUCED REGRESSION

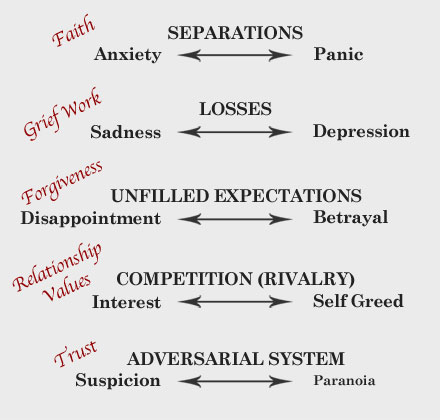

As previously stated, at one end of each continuum is a mild or predictable emotional experience or reaction and at the other an extreme or pathological one. The following comprise the five emotional continua:

Each continua represents the differing emotions that people experience during the divorce process.

Anxiety as the mild response leading to an extreme one of panic, the first continua, and sadness as the mild response leading to an extreme one of depression, the second continua, are attributed to the multiple losses and separations a divorcing individual has gone through and will go through during the process.

The typical feelings of disappointment evolving into more extreme feelings of betrayal, the third continua, are due to the human tendency to idealize people and situations in the early stages of our involvement with them and then later feel disillusionment.

Pursuing one’s reasonable self-interest developing into greed, the fourth emotional range, is played out during the divorce when the couple is dividing their assets during Equitable Distribution.

Moderate suspicion transforming into paranoia, the fifth emotional range, is an inherent component of the adversarial legal system and often infiltrates mediation.

Although all of these emotions are intrinsically distinct, they all have a common paradox: the reasonable emotions can all be experienced in a mature, reasonable manner in a divorcing situation, but divorce is often a regression-inducing event, and therefore these emotions are often carried to an unreasonable extreme.

The first and second emotional continua (anxiety to panic and sadness to depression) are closely related and can be discussed in conjunction with each other. These emotions are due to the multiple losses and separations a person going through a divorce encounters as the structure of their present world is dissolving. Separations elicit anxiety, and losses elicit sadness. Beginning at birth, separation and loss recur throughout life and anxiety and sadness are common emotions. In the framework of divorce, however, most people, whether they initiated the divorce, want the divorce, or feel victimized by it, are experiencing multiple losses and separations: loss of spouse who is often their best or only or oldest friend; of their residence; of friends; of extended family and/or loved in-laws; of a familiar lifestyle and way of looking at themselves in the world; separation from and/or loss of children; loss of financial security and/or the fear or illusion of it.

Ultimately, they are losing the world as they’ve known it, are alone and frightened, and sometimes driven to the point of panic or depression. In this extreme place, it is very difficult, if not impossible, for someone to make adult decisions and work in rational ways on their own behalf. In the context of seeking a divorce, this vulnerable state often lends itself to a wish for dependence on someone who promises to “take care of everything,” often an adversarial attorney.

The third emotional range (disappointment to betrayal) is due to a human tendency to become infatuated with people and situations early in a relationship, thus, setting ourselves up for disappointment, and, in the case of a regressed person, feelings of betrayal. During infancy and childhood, most people idealize one or both of their parents. The love, protection, and unending care which is received from this idealized or “good parent” often enables children to feel safer and surer of themselves and also enables a certain idealization of themselves. Marriage often unconsciously (and sometimes quite consciously) recreates for one or both parties the fantasy of the “good parent” in the person of the spouse or the marital situation itself.

The specific expectations do not matter; they could be material, emotional, social, economic, romantic and/or sexual. What matters is the degree of idealized hope and wish and promise which either or both spouses invest in the fantasy. Just as people realize with pain and anger the imperfections and shortcomings of their parents, with a divorce comes the regressive pain and anger of having again been disappointed to betrayed by the “good” parent. The regressed experience can be seen in the total devaluation spouses often make of the other and in the uncompromising rage and murderous, unforgiving feelings they experience towards them.

The fourth emotional range (self interest to greed) is played out in divorce due to the couple’s need to compete in dividing the marital assets in the process of equitable distribution. “Equitable” means “fair” and “Distribution” means “sharing” or “dividing” – “Fair Sharing” or “Fair Dividing.” It is generally in sibling relationships that people struggle and learn most about the issues of fairness, competition, and sharing. Because of the need to share the family’s resources and wealth, there is a pull to earlier sibling experiences and competitions.

Regressed sibling experiences define “fair” as getting what one wants and “unfair” as the other person getting what you want. Unresolved or partially resolved sibling experiences strenuously affect the equitable distribution of marital assets. Equitable distribution elicits at one end of the continuum a person pursuing their reasonable self interest, while at the other end the regressive feelings of envy, greed, feeling cheated, and all the difficulties involved in sharing and being fair. When feelings of envy and greed cannot be satisfied, destructive, spoiling behavior often follows.

When this form of regressive behavior spills over to the decisions related to the children, it becomes the basis for the most destructive and costly aspects of the divorce process. This becomes the story of King Solomon, perverted and modernized in a way where the baby is torn apart.

The last emotional range deals with distrust or suspicion on one end and paranoia on the other. The very existence of the adversarial system – waiting in the wings for the divorcing couple – creates a regressive pull towards distrust, and in the extreme, paranoia. While this assertion is certainly true for those people using adversarial attorneys, it is also true for people using mediation. For mediation clients, the possibility of the failure of mediation is a constant reality, particularly when they each recognize the power of their own and the other’s angers, hurts, fears, and destructive impulses. Also, many people in the couple’s life (the ever-present Greek chorus in divorce proceedings) are committed to the couple’s fight rather than the resolution of the fight. The suspiciousness – paranoia can also spill over onto the mediator as the perception of mediator bias. Mediators must recognize that the couple’s fear of the adversarial process is often an aid to moving the couple along in mediation.

This diagram depicts the divorce induced emotions described above and the experiences in the divorce process which elicit them:

DIVORCE INDUCED EMOTIONS:

ADVERSARIAL VS MEDIATED DIVORCE

The emotional ranges experienced by divorcing couples and individuals manifest themselves differently in mediated divorces as compared to an adversarial divorce. The adversarial divorce lends itself to the least mature, most regressive aspects of all these emotions with its emphasis on authority, dependence, power tactics, “winning as much as possible,” and defeating the opponent.

By defining the “best interests” of their clients in primarily monetary terms, matrimonial attorneys join with the least mature aspects of their clients regressed personalities. By pursuing win/lose situations, and by viewing the spouse in exclusively adversarial terms, regressive experiences in regards to separation and loss, rivalrous sibling relationships, and suspicious paranoia are intensified.

By promising to “take care of everything” and by assuming exclusive control of the negotiations , the adversarial process encourages a dependence which is not ultimately fulfilled and which leaves clients feeling betrayed and abandoned by their attorneys and the court, as well as their spouse, after “everything” is in fact not taken care of.

While couples in mediation are also involved in their own individual regressive experiences, the mediator can intervene in several different ways to help the couple cope with their fears and rages, their greedy and vengeful emotions, their feelings of having been betrayed and cheated.

Mediation differs from the adversarial process in numerous way. It is unique in that both parties enter into it together; the joint presence (the “magic of mediation”) prevents many negative assumptions, fears, and projections. Also, the couple can explore alternatives to divorce at any point in the process, as compared to litigation. Additionally, the accepting, non-blaming, empathic posture the mediator maintains towards both spouses encourages similar treatment of each other.

It is clear that the mediation process itself blocks and discourages much of the regressive process and tendency towards extreme emotions. This is accomplished because the process itself mobilizes and strengthens adult ego functioning in the following ways:

- It encourages and enables adult problem solving and decision making behavior;

- It allows a controlled amount of emotional ventilation about and towards each other;

- It allows and enables the negotiating process to take place between the spouses and themselves;

- It encourages the kind of trust which develops from open disclosure to each other;

- It reminds them that they are not getting divorced from their children and it helps them focus on the needs of their children;

- It consistently has faith in the couples ability to create win/win solutions.

These aspects of mediation are enormously beneficial to the divorcing couple during the divorce process. Mediation, however, is not entirely limited to influencing the couple solely during the mediation sessions. The skills gleaned during mediation can be utilized by the couple in future interactions with each other and others. There are different conceptual models for mediating; different paradigms for viewing the mediation process.

MODELS OF MEDIATION

For much of this next section I am grateful to all the contributors to the Mediation Quarterly, Fall 1993, particularly Donald T. Saposnek. In his article, “The Art of Family Mediation,” Dr. Saposnek presents a four level analysis for viewing the mediation process. The following section is my interpretation and expansion of his framework).

Level 1: Where Conflict is Seen as an Opportunity to Solve a Problem or Resolve a Conflict

Simply stated, all mediation includes this and all mediators do this. It is on this level that mediation is seen as the better alternative than the adversarial process for divorce and it is in this way that we present mediation to the public. Training programs in divorce mediation all address this level of conflict resolution, since this is what most people see as the purpose of mediation. In this view, mediation is seen as linear, logical, analytic, task-oriented, and often mechanistic: a conflict seeking a solution. Even without mediator-conscious intentionality, the mediation process done on this level still blocks a good deal of the emotional and developmental regression which would otherwise take place in an adversarial divorce.

Level II: Where Conflict is Seen as an Opportunity to Teach Couples How to Resolve Conflicts

All mediators teach couples how to resolve conflicts and how to negotiate, regardless of whether they intend to teach this element or not. Most mediators recognize this and lend themselves deliberately to this process. Some mediators see themselves as teaching in order to expedite the mediation itself while others see themselves doing this because they recognize that this will serve the couple well in their future relationship with each other, with their children, and perhaps, with others. Some people refuse to learn to do this and some mediators (who define their function exclusively on Level I) refuse to deliberately teach this. But regardless of the mediator’s intentions, this kind of learning almost always takes place. With more mediator consciousness intentionality, however, this teaching/learning process enables more opportunities to be found and expanded within the mediation process.

Mediation provides a wonderful opportunity to teach many skills within its context:

- Communication skills

- Problem solving and decision making skills

- Negotiation skills

- Parenting skills

- Money management skills

Level III: Where Conflict is Seen as an Opportunity for the Blending of Needs

Simply stated, conflict can be seen as an opportunity to compromise or as opportunity to determine the real needs of each of the parties in order to create solutions which go way beyond compromises or the mutual, even equitable sacrificing of needs. This is truly believing in and going after the WIN/WIN solutions. The ability to see and to teach couples how to see conflict as an opportunity for the blending and integrating of needs, is one more area of teaching available within the mediation process.

Level IV: Where Conflict is Seen as an Opportunity for Healing

It is on this level that we can now return to the divorce induced, regression fueled, emotional experiences discussed initially and see how as mediators, without doing psychotherapy, we can powerfully aid a healing process in regards to these emotions. Again, I want to say that with or without intentionality all mediators (except the most task oriented and controlling) are frequently initiating and supporting healing behaviors and energies in the mediation. They do this by allowing the couple a certain amount of room for ventilating feelings of anger, grief, distrust, etc. and by being accepting, empathic, and even at times, compassionate. All of these mediator behaviors promote healing and with more conscious intentionality, more healing, and more specific healing can take place.

HEALING ENERGIES IN MEDIATION

Before discussing specific healing energies in mediation, I want to differentiate healing from psychotherapy. First of all, a patient or client in psychotherapy knows they are there for personal growth, change, development, or something which has to do with some kind of alteration in their psychological, emotional, or personal behavioral situation. This is not true for mediation clients or they have come to the wrong place. For example, a patient in psychotherapy is struggling with anger. The therapist and patient identify the feeling as anger and explore it together. They deepen their understanding of it and often analyze it both historically and in the patients contemporary life looking at how it manifests itself in the patient’s relationships and life contexts (often past and present) and in relation to the therapist and therapy situation itself. Not all therapies do all of this but all therapies do some of this. This process is what I am calling a vertical approach to the emotional experiences I presented before. Healing, on the other hand, is a horizontal process and involves none of this exploration or analysis. This horizontal healing process occurs in mediation and in life with or without the mediator consciously participating. But, with a mediator’s purposeful intent, this is a powerful aspect of mediation that takes it beyond simply being a better way of getting divorced.

Using this horizontal paradigm of healing, I would like to now explore each of the five continuum of emotional experiences in order to see how people going through mediation can be assisted in their attempts to heal from divorce induced emotional experiences. The first emotional range involves anxiety and some fear at one end of the continuum and panic on the other. We looked at this before as due to the many separations involved in divorce and the feeling of being lost in a scary new world. In my experience as a mediator the healing antidote for these feelings of anxiety and fear is for the person to have FAITH in themselves and in their future. This is how people heal from fear. Mediators who have faith in this person can find ways of expressing and demonstrating it – Faith in their ability to mediate and work things out; faith in their ability to parent their children in new ways; faith in their ability to get on with their lives, heal their wounds, develop a new relationship with each other, establish new and perhaps more lasting relationships with others; faith in their ability to recover from the divorce and be at peace again in life. Some of this may be expressed directly at the right time in mediation and some of it may be communicated in attitude or style, but the more conscious intention and open heart the mediator brings to this, the more they will impact on this.

The second emotional range involves feelings of sadness on the one end to depression on the other. We looked at this before as being in reaction to the multitude of losses one experiences going through divorce. The horizontal antidote for these losses and the emotions they create is to do GRIEF WORK – to MOURN. This is how people heal from loss. The mediator can allow for some of this grief work to occur in the mediation since there is a great deal of room in mediation for the expression of sadness about loss. The mediator can actively validate these feelings, empathize with the pain, express authentic compassion, or simply hear and accept these expressions similar to the way one sits by the side of a grieving friend. This is a healing process.

The third emotional range involves feelings of disappointment and some anger at one end to feelings of betrayal and rage at the other due to unfulfilled expectations, wishes, fantasies and promises inherent in the failed marriage. The horizontal antidote for these emotions is FORGIVENESS. This is how people heal from anger. Mediators can find opportunities to inject this idea of forgiveness into the work both directly and in subtle indirect kinds of ways that stray from lecturing about forgiveness. Often in talking about the children, for example, it is easy to see how they are angry and seemingly “unforgiving” of one or both of the parents. Mediators can simply use the terms “not being forgiving” or “being unforgiving” often in the place of the word “angry” and subtly teach the couple a great deal about the process of healing from anger. Mediators can express faith in the idea that others will or do forgive. Often this kind of discussion about others in the couple’s Greek Chorus enables the couple to talk about their own needs or abilities to forgive or be forgiven by each other. The mediator can also express faith in the couples ability to forgive each other over time. Often, an opportunity for the mediator to inject the idea of forgiveness is when the couple is clearing up misunderstandings or different perceptions they each had had and the angers or hurts these had created. A caveat, though: for some people it is easier to forgive than to accept being forgiven!!

Forgiveness is the best alternative to anger in that it releases the angry person from being upset and feeling like a victim – it is voluntary so that it empowers the forgiver and enables the forgiver to give up suffering. In other words, forgiveness is not really for the forgiven as much as it is for the one doing the forgiving. Often, forgiveness is what is needed for the couple to emotionally separate. When being married in affection turns into being divorced in anger, the couple is often more attached and involved with each other in hate than they ever were in love. Forgiveness frees them from each other and enables them to truly separate from the negativity and get on with their lives.

The fourth emotional range involves feelings of self-interest on the one hand to uncontrolled greed on the other. We looked at this earlier as coming out of the need to compete with each other in equitable distribution and the rivalry this elicits. The antidote for greed is placing value in something else. In the case of divorce, often recognizing the value in the relationship with each other or with mutually cared for others (like their children) is the remedy. Most people getting divorced continue to remain connected to each other emotionally and spiritually as well as in a real, physical manner after the divorce. The healing here is in recognizing the ongoing CONNECTION and in learning to value it – in the shadow of the separation is a continued connection. In the shadow of their marriage was their eventual separation – if not now in divorce, then eventually in death. And, in the shadow of their separation is their future connection. When they can reconnect with each other in new ways (as co-parents, or, perhaps, as two sad or scared or disappointed people who have to grieve their losses, overcome their fears, and get on with their lives) – when they can recognize that even if they never see each other again they remain connected – even if only in the memories which only they share – when they recognize that even in separation there is ongoing connection – then the healing in relation to many of the issues I have been discussing happens.

The mediator helps this process by continually communicating relationship values and by understanding and finding ways to communicate that even as the couple separates and has to get on with their own lives, they will remain connected. There is no contradiction in recognizing that the couple has to get on with their own lives and remain connected to each other into the future. The real question is what will be the nature of the connection, and the mediator (with conscious intentionality) can help the couple begin the process of answering that question.

The fifth emotional range involves feelings of suspiciousness and some distrust on the one end to full-blown paranoia at the other. The truth is that these people are engaged in a process that has long term meaning for them legally, financially, emotionally, spiritually, etc. and since they feel and perhaps, are competitive with each other in some of these regards they have reason to be suspicious of each other. The horror stories often told of people’s dealings with the adversarial divorce process have these people much more distrustful and fearful of each other than they need to be. The healing antidote for distrust is learning to TRUST and mediation fosters trust by encouraging increasing degrees of risk-taking in open disclosure. The more open, the more honest the couple can be helped to be, the more basis for trust develops. When confusions, disagreements, or difficulties between the couple starts turning into distrust, the mediator must be prepared to reframe what is going on between them accurately and help the couple understand that their seeing things differently need not be a basis for losing trust. By reframing in such a way as to experience the good in these people, in their circumstances and in their intentions and by finding ways to trust these people with ourselves, we as mediators aid their healing. In this regard, conscious, purposeful, appropriate mediator openness and disclosure can further aid healing in this dimension.

What enables people to heal from the divorce process is faith, forgiveness, relationship values, grieving and trust. Even as healing from divorce is an emotional process, it is also a spiritual process. Marriage and divorce were traditionally seen as a spiritual or religious event. Historically, religion has been used to define and determine both divorce and marriage, and, it is a somewhat modern notion that marriage and divorce became the province of the legal profession. As mediators, we have to go beyond the legal profession in what we understand to be our areas of focus and concern. Mediation is the field of practice that puts spiritual values and meaning back into divorce, and as I have said before, this happens in all mediation but can be intensified and enriched with mediator conscious intentionality…and an open heart.